7 Differences between complex and complicated

Decision-makers commonly mistake complex systems for simply complicated ones and look for solutions without realizing that ‘learning to dance’ with a complex system is definitely different from ‘solving’ the problems arising from it. — Roberto Poli

Many people believe that complexity is just higher order complicatedness i.e. that there is a continuum and that the difference is one of degree, not type. When one considers however how very different these states are from each other, I tend to agree with Dave Snowden when he says that there are in fact phase shifts between them i.e. they are fundamentally different types of systems.

Why is this important: as long as decision-makers believe they are dealing with complicated systems, they will assume they are able to control outcomes; find solutions to problems and waste a lot of money on expert consultants to give them the “answers”. For organisations to become more resilient and sustainable, business science simply has to move beyond its Newtonian foundations towards an understanding of complexity.

Roberto Poli articulates the difference between complicated and complex as follows:

Complicated problems originate from causes that can be individually distinguished; they can be addressed piece by piece; for each input to the system there is a proportionate output; the relevant systems can be controlled and the problems they present admit permanent solutions.

On the other hand, complex problems and systems result from networks of multiple interacting causes that cannot be individually distinguished; must be addressed as entire systems, that is they cannot be addressed in a piecemeal way; they are such that small inputs may result in disproportionate effects; the problems they present cannot be solved once and for ever, but require to be systematically managed and typically any intervention merges into new problems as a result of the interventions dealing with them; and the relevant systems cannot be controlled — the best one can do is to influence them, or learn to “dance with them” as Donella Meadows rightly said.

Let’s look at these in more detail:

1. Causality

Complicated: Linear cause-and-effect pathways allow us to identify individual causes for observed effects.

Complex: Because we are dealing with patterns arising from networks of multiple interacting (and interconnected) causes, there are no clearly distinguishable cause-and-effect pathways.

Implications: Root cause analysis is largely a waste of time in a complex system. Yet, how often have you heard a decision-maker express a need for exactly that?

2. Linearity

Complicated: Every output of the system has a proportionate input i.e. Newtonian physics apply.

Complex: Outputs are not proportional or linearly related to inputs; small changes in one part of the system can cause sudden and unexpected outputs in other parts of the system or even system-wide reorganization.

Implications: Large multi-million dollar change initiatives can have zero impact, while one wrong word in an email (or one image on a T-shirt a la H & M) can lead to a system-wide revolt. Small safe-to-fail experiments are more useful than large projects designed to be fail-safe)

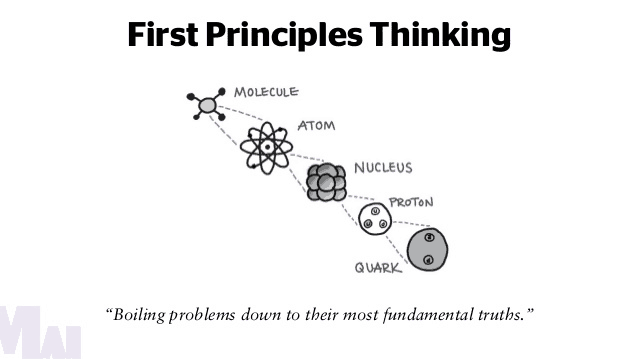

3. Reducibility

Complicated: We can decompose the system into its structural parts and fully understand the functional relationships between these parts in a piecemeal way.

Complex: One cannot assume that one structure has one function as the structural parts of the system are multifunctional i.e. the same function can be performed by different structural parts. These parts are also richly inter-related i.e. they change one another in unexpected ways as they interact. We can therefore never fully understand these inter-relationships.

Implications: Too many management, problem-solving and OD methods assume that a problem and/or system can be deconstructed into its component parts, understood, optimised and fixed. Just think of our favorite change tool: the restructuring, which is believed to be the cure for any change problem. Complex systems are emergent, they are greater than the sum of their parts … we need to interact or “dance” with the system in order to be able to influence it, and we also need to understand that our mere presence is already changing it. Our attempts to reduce and re-arrange will fundamentally change or even destroy the system properties we hold most dear, like culture and resilience.

4. Controllability and solvability

Complicated: Systemic contexts and interactions can be controlled, and the problems they present can be diagnosed and permanently solved.

Complex: Complex problems present as emergent patterns resulting from dynamic interactions between multiple non-linearly connected parts. In these systems, we’re rarely able to distinguish the real problem, and even small and well-intentioned interventions may result in disproportionate and unintended consequences.

Implications: These systems are prone to high levels of surprise, uncertainty; and interventions (even simply observing the system) causing unexpected changes and even new or worse challenges. We need to shift from “problem & solution” thinking to “patterns & evolution”. This serves as a particular challenge to the Design Thinking community.

5. Constraint (openness)

Complicated: the reason why the “one structure-one function” assumption is valid in complicated systems is that their environments are delimited i.e. governing constraints are in place that allows the system to interact only with selected or approved types of systems. According to Poli: “functions can be delimited either by closing the system (no interaction) or closing its environment (limited or constrained interactions).”

Complex: complex systems are open systems, to the extent that it is often difficult to determine where the system ends and another start. Complex systems are also nested they are part of larger scale complex systems, e.g. an organisation within an industry within an economy. It is therefore impossible to separate the system from its context.

Implications: Context matters, ignore it at your peril. As soon as organisations become too internally focused, the naval gazing makes them vulnerable. Making sure that adequate and diverse feedback mechanisms are in place is a key strategic imperative.

6. Knowability

Complicated: These systems, because they are closed and can be deconstructed can be fully known or modeled.

Complex: I think it was the physicist Murray Gell-man that said: “The only valid model of a complex system is the system itself.” The complexity of a system is not dependent on the amount of available data or knowledge. We cannot transform complex systems into complicated ones by spending more time and resources on collecting more data or developing better theories.

Implications: The only way to truly understand a system is to interact with it. Data has seduced many decision-makers into thinking they can understand their organisations from a distance … comfortable in their ivory towers, they make decisions with far-reaching consequences without having any real understanding of the potential impact of these decisions. Similarly, big data has been a big focus for many organisations to understand their customers. While it certainly has value, big data and related collection methods raise serious moral and ethical concerns. Its value is also limited: big data can tell you where I’m going, when, how much I am spending and the payment methods I use … but it cannot tell you why I am doing and my motivations. So in short, get closer to the system, interact with it and over time you will gain a better understanding of the emergent whole, not only the parts.

7. Creativity and adaptability

Complicated: complicated systems need an external force to act on them in order to introduce change.

Complex: these systems are able to observe themselves, learn and adapt. They are creative. According to Poli, “Everything changes, but not everything is creative. To mention but one component of creativity, the capacity to (either implicitly or explicitly) reframe is one of the defining features of creativity. Creativity also includes some capacity to see values and disvalues and to accept and reject them. Therefore, it is also a source of hope and despair. None of these properties are possessed by complicated systems.“

Implications: complex systems are adaptive and able to learn. In human complex systems intentionality, identity constructs and intelligence also play a role. People tend to resist re-organisations, top-down change initiatives and the introduction of new ways of work that include new roles like SCRUM. These all lead to a disruption of social dynamics and structures that can have significant unintended consequences e.g. people can pretend to conform, but sabotage the change process in subtle ways. But similarly, given the right enabling constraints, and freedom to adapt in context-relevant ways, the people in these systems can be mobilised to evolve in unexpectedly beneficial ways.

This is not a complete list, there are many other differences to explore but I hope these reflections are useful for facilitating a better understanding of these different systems, and how to act in them in appropriate ways. It is also important to note that in most human systems, complex and complicated co-exist i.e. you find complicated problems in complex systems and complex problems in complicated ones. Sense-making frameworks like Cynefin are useful to help leaders make identify the context they are dealing with.

References: A Note on the Difference Between Complicated and Complex Social Systems, Roberto Poli, 2013

📝 Read this story later in Journal.

🍎 Wake up every Sunday morning to the week’s most noteworthy stories in Wellness waiting in your inbox. Read the Noteworthy in Wellness newsletter.